Rainbow wisdom and words from a past hero

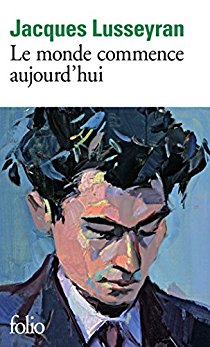

While competing at a Toastmasters speech contest in Paris last April, I heard a fellow competitor discuss three books which changed his life. One of the those books intrigued me because it was written by a blind man who, after surviving over a year in the Buchenwald concentration camp, eventually became a French professor in the USA. A singular destiny indeed! That very evening I bought a copy of the book called Le monde commence aujourd’hui, which unfortunately is not available in English.

I only had to read a few pages to discover, I was on the same wavelength as this hero of the French Resistance, this departed soul – this blind man who writes, “The eyes create color” and, “The eyes make color”. And yet, it was only further into the book that I saw the full connection to my speak-the-rainbow theory. On page 94, I stumbled on an ode to the act of public speaking which totally resonates with all that I wish to communicate through my blog. For that reason, I am proud to introduce you to Jacques Lusseyran, a man who writes so beautifully about the “sacred” act of public speaking. The quotes below are taken from a translation by Wayne Constantineau of Lusseyran’s writing on the act of speaking which can be found here.

On audiences we should remember:

The public never fails to love the speaker. That is its job! It likes him instinctively; limping, haggard, in tatters, elegant or authoritarian. The audience grants him speech in a great outburst of sensibility. It waits with an abandon that resembles hope.

Let me be frank: the audience does not listen, it waits. It waits for him to do something with it, and especially for it.

On the act of speaking we should remember:

For the true presenter, speech borders on the solemn, on the sacred.

No, I don’t hold words as sacred. The poor things are always paltry, simultaneously false and true, and in a proportion that defies all measure. But speech, this act of pronouncing and stringing words together in the presence of someone else, for someone else, is sacred.

On silences we should remember:

Speech is made from silence. Speech provides humanity with its most privileged means of making silence heard. The public never listens to someone who never interrupts himself. It does not hear him any more. So, to speak well the presenter must first attend a rude school where he learns to shut up.

The speaker must stop. The best is to do it in a quiet mood, that is to say, attentively. The speaker must stop because the meeting with the listener takes place in this interval. Speech is born in this short silent space.

In this pause–however small as it may be–the speaker says everything that he has to say.

On stage fright we should remember:

Some people think of stage fright as a professional sickness when actually it is a moral fault, a lack of good sense: excuse me for stating it so bluntly. I myself have had stage fright, and I know that I alone was responsible for it.

Quite simply, I refused to leave my burrow. The audience, only a few feet away, beckoned me. I refused to come out. I refused to see it. I went back to my ideas, my thoughts, the whole baggage of knowledge or the intentions that I had brought with me to the courtship. I reviewed the parts of my speech. I mentally verified the details. I replayed ahead of the fact the various merits–so big a while ago and suddenly so small–of what I was going to say. In brief, I looked at myself, myself alone. I saw myself as the centre of the world.

This unconscious refusal to take the audience into account means that I momentarily forget the very thing I am there to do.

I also forget that my function is not to be seen or to show off but to speak, and that speech does not belong to me alone.

On the need to love your audience we should remember:

Were a speaker to continue without love, he would be adding foolishness to his ingratitude. Arming his speech with love provides the only chance that his science or talent can be understood or recognized. Were he the most intelligent of men, the loveless speaker scares his public, puts it into flight. He may be listened to–out of politeness or even out of interest–but with that incurable distancing of spirit that is so pervasively seen on the faces of people watching television.

On flow and connection with the audience we should remember:

Like a complete physical and mental organism, each audience emits its own specific heat. In shop talk among those who deliver speech by trade, we hear expressions like “take the temperature of the hall.” The speaker, the actor, the professor must go beyond just knowing that it exists; he must perceive it, then follow it. And that creates a whole spectacle in itself.

Currents of attention or distraction, excitement or fatigue, dream or reverie, and moments of comprehension displace each other continuously. The true speaker follows them, like a doctor examining a patient. He prods, he gropes, he touches. He has the right to, since the audience demands it. And most of all, he should fear nothing.

The true presenter knows that he and his words do not count for much, and that his person–exemplary as he may be–does not count for much more. For him, the whole work consists of launching words from inside himself.

Here, a simple act of confidence bridges the gap, or, better still, an act of abandon. Not to the public–it has nothing to do with this passive act–but to speech. Now is the time to let it come and to flow through me.

I do not create speech by speaking. It already exists and it readily renders its words and rhythms. It requires only that I don’t oppose them. I must be ready to receive them. I must know my subject well, for example: I must have thought of it precisely and often, and before coming. With all urgency, I must now attend to the audience for it is now waiting.

Thank you Jacques for these words. We are ready and armed with your wisdom to face, serve, and connect with the audience which is waiting.